[advanced_iframe securitykey=”5870105317bee1454e210fffd43d74b89a88430f” src=”http://statisticsblog.com/popchart.html” width=”600″ height=”550″ scrolling=”yes”]

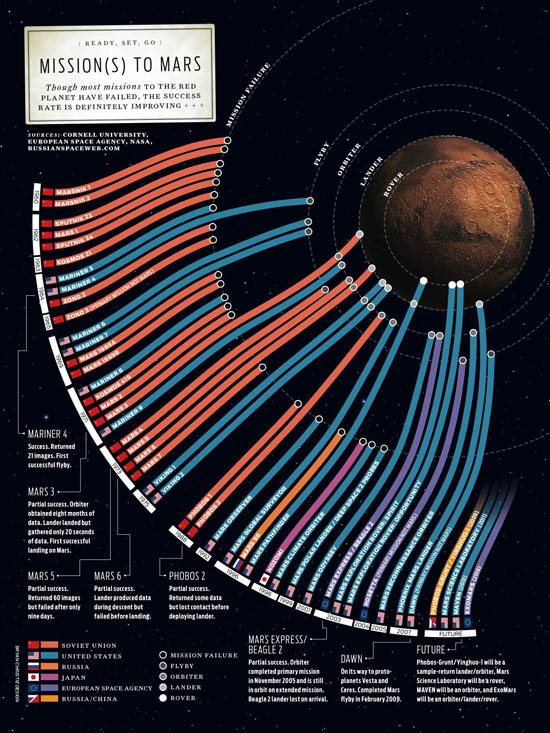

My daughter, who turns 10 in April, has discovered pop music. She’s been listing to Virgin Radio 99.9, one of our local stations. Virgin provides an online playlist that goes back four days, so I scraped the data and brought it into R. The chart shown at top shows all of the songs played from February 17th through the 20th, listed by frequency.

Broadly speaking, the data follows a power law. But only broadly speaking. Instead of a smoothly shaped curve from the single most frequently played song to a tail of single plays, Virgin Toronto has four songs that all share the heaviest level of rotation, then a drop-off of almost 50% to the next level. There was one big surprise in the data, at least for me. Listening to the station, it seems like they are playing the same 10 songs over and over. This impression is true to some extent, as the top 10 songs represented about one-third of all plays. But in just four days there were 57 single plays, and 44 songs played just twice. In all, 173 unique songs were played, with a much longer tail than I had expected.

That said, it would be interesting to compare Virgin’s playlist distribution with the widely eclectic (at least to my ears) Radio Paradise. Anyone want to give it a try? Here’s my code after I scraped the four pages of data by hand and put them into a text file.

To get the link to the Youtube videos, I used Google’s “I feel lucky” option paired with a search for the song name. If you get an unexpected result, take it up with Google. In the past I’ve used R’s “brew” library to generate HTML code from a template, this time I just hand coded the snippets. To make the red bars I found out the maximum number of plays for any song, then stretched each bar relative to this maximum.